FLASHPOINTS: DNS Detour: Malaysia's Contentious Venture into Digital Governance

Malaysia's DNS redirection mandate sparked controversy over internet freedom and security. The policy risked cybersecurity vulnerabilities and internet fragmentation. Though rescinded, it highlights the challenge of balancing security with open internet access.

Bottom line up front:

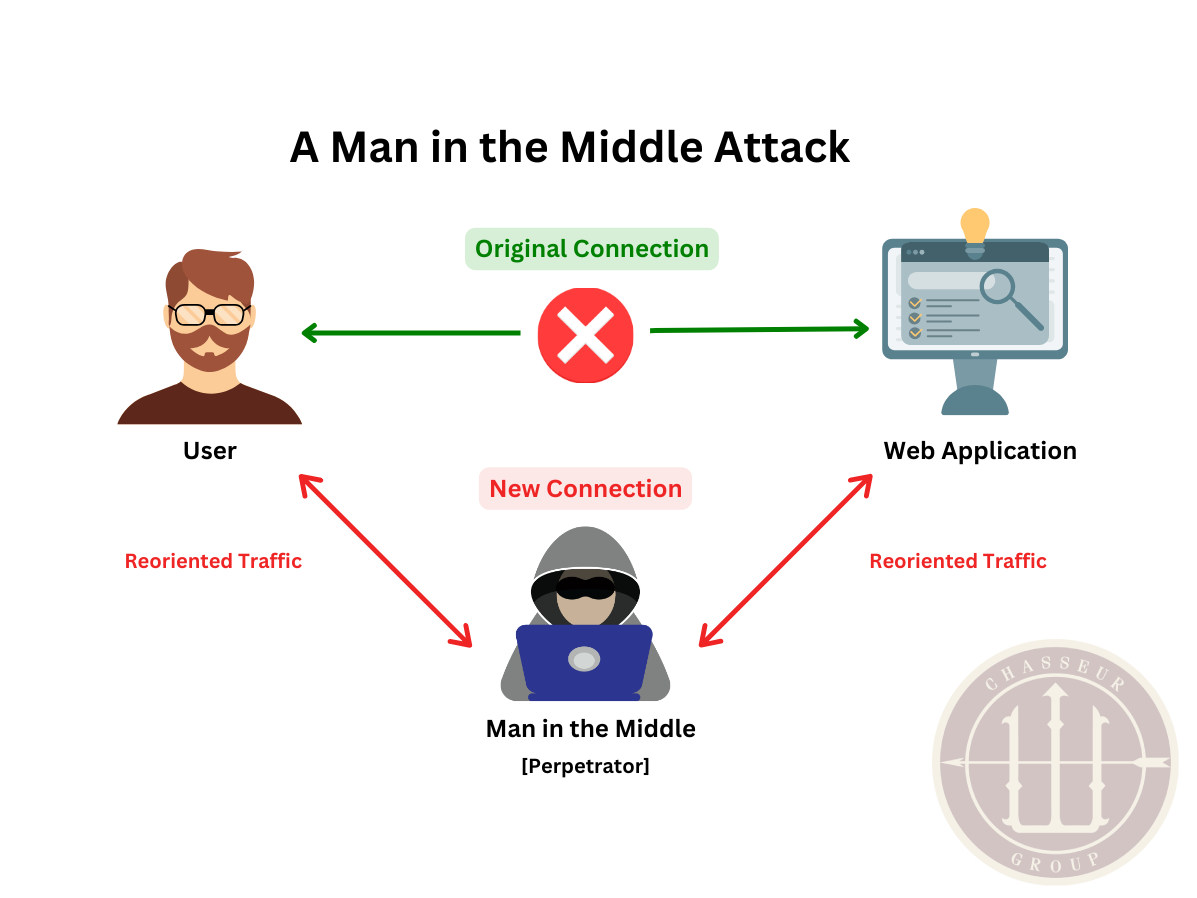

- The MCMC's attempt to mandate DNS redirection for ISPs in Malaysia, aimed at filtering harmful content, has raised significant concerns about internet freedom, privacy, and security risks, including potential man-in-the-middle attacks.

- The DNS redirection policy could introduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities by redirecting DNS services for millions of Malaysian internet users, potentially creating a concentrated target for cyberattacks and neglecting diverse user needs.

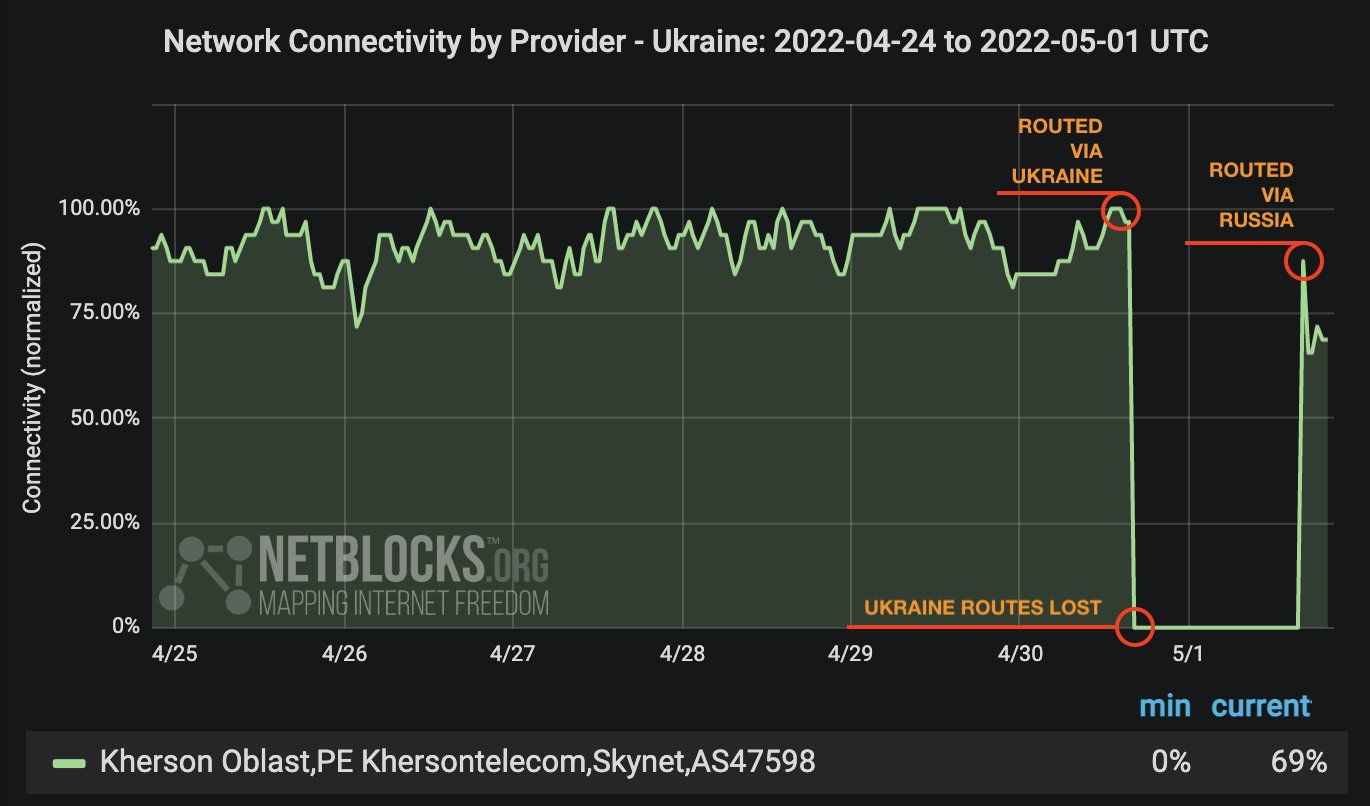

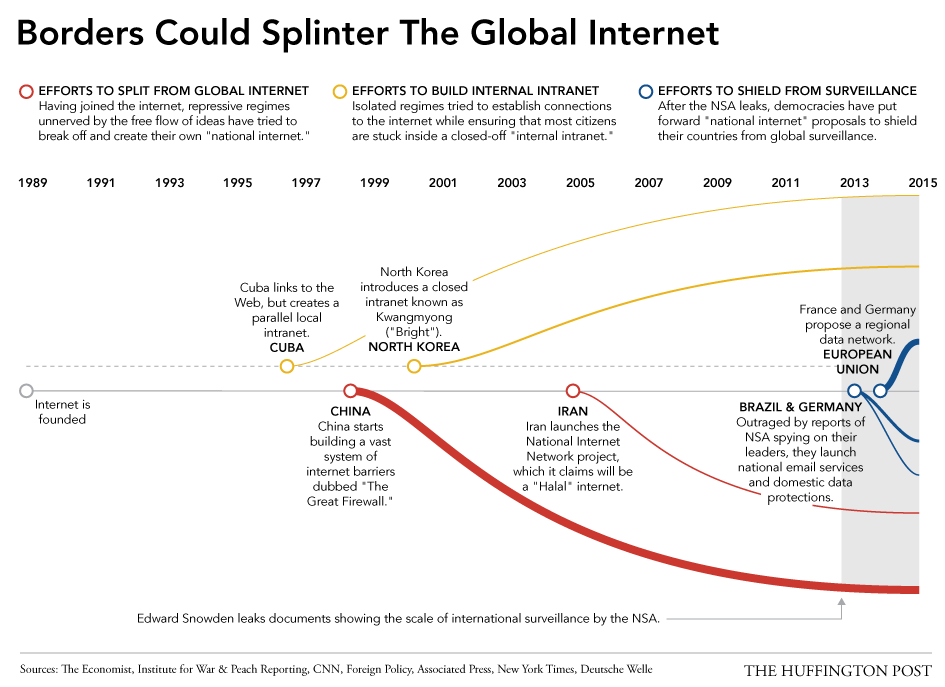

- This policy represents a step towards internet fragmentation or 'splinternet', which could have far-reaching implications for Malaysia's digital economy, potentially deterring international tech investments and hindering innovation.

- Although the mandate has been rescinded due to public pressure, the incident highlights the need for a more nuanced, comprehensive approach to internet governance in Malaysia that balances cybersecurity concerns with the preservation of an open, accessible internet.

In a bid to create a safer online environment, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) had attempted to mandate all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to implement public domain name service (DNS) redirection by 30 September for businesses, enterprises, and government entities. The stated objective of this measure was to filter out access to harmful sites, including illegal streaming, pornography, and scams. While Maxis and TIME had reportedly initiated this implementation since August, the controversial mandate had sparked considerable debate and faced substantial backlash from online users, specifically digital rights advocates and members of the local tech communities on X, Reddit and Lowyat Forum.

Prior to this, Sinar Project, a tech advocacy group, had raised the alarm about potential security risks after discovering that certain ISPs, including Maxis, covertly rerouted DNS queries meant for external services to their own servers. By September 5, 2024, the DNS redirection was widely publicised by local media and ignited a long-simmering online backlash, amplifying citizens' fears that the measure would not only impair website accessibility but also curtail the free flow of information.

Malaysia's latest attempt at DNS redirection policy represents a troubling step towards internet splintering, threatening the open and interconnected nature of the global internet. This measure extends far beyond simple access restrictions, potentially causing technical issues, disrupting services, and inadvertently blocking legitimate content. The opaque nature of the process complicates appeals and raises serious questions about internet governance in Malaysia. The latest furore serves as a lesson on internet governance and underscores the complex balance between security and open internet access.

Understanding DNS Redirection and Its Issues

At its core, DNS involve rerouting DNS requests from one server to another. While DNS servers typically translate domain names into IP addresses to locate websites, DNS redirection would allow ISPs to divert requests for specific websites to different servers, ostensibly to enforce access restrictions. DNS redirection is also known as domain name hijacking. This mechanism carries significant implications for internet freedom and privacy. More crucially, the DNS redirection effectively created a form of sanctioned man-in-the-middle (MiTM) attack, potentially exposing users to significant vulnerabilities.

To fully grasp the impact of this mandate, it's essential to understand the three main DNS protocols currently in use. The oldest and most basic protocol uses plain text without encryption. More secure options include DNS over TLS (DoT), which uses encryption on a separate port, and DNS over HTTPS (DoH), which operates on the same port as HTTPS traffic. DoH is specifically designed to make DNS queries indistinguishable from other HTTPS traffic, making it challenging to block without affecting other services.

The implementation of DNS redirection by the country’s national telecommunication infrastructure, Telekom Malaysia's (TM) network, illustrates the potential pitfalls of this approach. Following the directive, TM’s decision to block Cloudflare's DNS IP address entirely, including the HTTPS port, inadvertently caused widespread issues that extended beyond DNS queries to potentially affect other HTTPS traffic as well. This approach, which limits users' ability to access information freely and potentially compromising privacy through the redirection of requests intended for third-party DNS services to local servers, DNS redirections elicit profound worry about transparency and control over internet traffic.

The mandatory DNS redirection policy for ISPs in Malaysia could introduce significant cybersecurity vulnerabilities. By redirecting DNS services for approximately 33 to 35 million internet users in Malaysia, this approach might create a concentrated target for potential cyberattacks. Whilst major DNS providers like Cloudflare and Google are not immune to outages and attacks, they would represent only a fraction of available DNS servers. Many alternative DNS services would continue to offer unique features, such as customisable blocking for parental control or ad filtering. The policy's implementation is expected to neglect the diverse needs and preferences of users, forcing them into a one-size-fits-all solution. Moreover, given the historically tepid response to cybersecurity threats from both Malaysian corporations and government entities, there are justified concerns about the robustness of these centralised DNS systems against sophisticated attacks. This situation may potentially expose millions of users to increased risk, possibly undermining the very security the policy purports to enhance.

Splinternet Explained: Potential Economic Fallout and Broken Knowledge

Malaysia's DNS redirection policy epitomises the phenomenon of internet fragmentation, commonly known as 'splinternet'. Splinternet arises from a complex interplay of political, technological, and regulatory disparities among nations, effectively fracturing global connectivity and impeding digital commerce. The economic ramifications of this fragmentation are twofold. First, businesses will face an increasingly labyrinthine landscape when expanding into new markets, as they must navigate a patchwork of regulations that complicate international strategies. Second, restricted access to global platforms stifles innovation and competition, with smaller enterprises bearing the brunt of these limitations.

On a societal level, the splinternet erodes the concept of a unified global public sphere. As national borders increasingly dictate access to information and communication channels, isolated digital enclaves emerge. This fragmentation provides fertile ground for censorship and control, particularly in authoritarian regimes where restricted access to global information sources suppresses the free flow of knowledge. If Malaysia continues to pursue this path, it risks isolating itself from the global digital ecosystem and potentially stunting its own technological and economic growth.

The blocking of encrypted DNS protocols like DoT and DoH had provoked an outcry from the local tech community, as it undermines a collective effort to enhance online privacy and security. This shift transforms ISPs from neutral conduits into active gatekeepers of internet traffic, profoundly impacting digital security. If ISPs begin to intercept encrypted traffic, they could potentially compromise the security of sensitive sites, including financial institutions.

Moreover, this policy conflicts with Malaysia's ambitions to attract global tech investments. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim's data aspirations face jeopardy as companies like Nvidia and AWS may reconsider establishing their data centres in a country with questionable internet freedom and security practices. This underscores the delicate balance between public safety concerns and fostering a vibrant digital economy.

Middle-Power Aspirations Meet Digital Realities: Malaysia's Tightrope Walk in Cyberspace

The MCMC has a history of imposing website restrictions without prior notice. A particularly striking instance occurred during the 2018 elections when Malaysiakini's live results platform was abruptly taken offline, allegedly through DNS manipulation. Other targets of previous blocks included MalaysiaKini’s Undi.info, Sarawak Report, and AsiaSentinel. In the wake of the initial DNS redirection initiative, unintended consequences emerged, including the inadvertent blocking of legitimate services such as the Cloudflare Dashboard, crucial for many tech professionals. The ripple effects extended to the gaming and creative communities, with local artists and designers voicing frustration over their inability to access ArtStation. When questioned, authorities cited a request from the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs, claiming copyright infringement as the rationale for the block. Moreover, MCMC attempted to dismiss valid criticisms by characterising them as "misinformation".

This latest digital governance misstep represented a critical juncture in Malaysia's digital landscape, with far-reaching implications for internet freedom, national security, and economic development. This policy underscored the complex challenge of balancing cybersecurity concerns with the preservation of an open, accessible internet. The mandate's implementation would have necessitated a significant overhaul of existing systems and user behaviours, effectively rebuilding the architecture of Malaysia's cyberspace. This monumental task not only posed technical challenges but also raised serious questions about privacy, data security, and the potential for abuse.

The approach by the Minister of Communications Fahmi Fadzil along with MCMC to internet governance seemed to leverage public safety as a justification for fragmenting Malaysia's internet. This is particularly evident in light of their attempt to introduce licensing framework for social media and private messaging platforms, a move that drew criticisms from prominent tech companies that warned of potential harm to the country’s digital economy. Rather than pursuing comprehensive, evidence-based policy solutions to address the root causes of online threats, the authorities opted for the blunt instruments of bans and redirections. While these measures might offer short-term fixes, they would fail to address deeper social issues that contributed to online risks.

Effective resolution of these challenges would have required a holistic approach, involving the re-engineering of both internet infrastructure and user attitudes towards security. This underscores the complex nature of internet governance, which typically engages a network of international stakeholders, including civil society, private sectors, and governments working collaboratively to develop policies for critical internet technologies. However, while such an approach is technically feasible, it may not be realistic for Malaysia given its middle-power status. The country faces the challenge of balancing its aspirations for digital advancement with the practical limitations of its geopolitical position and resources.

Why it matters

This pattern of behaviour provoked deep unease about transparency and due process in the MCMC's content regulation practices. Moreover, this policy could have significantly impacted Malaysia's aspirations to become a leading digital economy in the region. The potential for increased government intervention in internet traffic may have deterred international tech investments and hindered innovation. As Malaysia navigated these challenging waters, it needed to strike a delicate balance between protecting citizens online and preserving the fundamental principles of an open internet. The outcome of this policy would likely have set a precedent for internet governance in Malaysia and potentially influenced similar decisions in other countries, underscoring the need for a nuanced, comprehensive approach to cybersecurity that considered long-term implications for democracy, economic growth, and technological progress.

The latest announcement has declared that the DNS redirection mandate has now been rescinded due to strong public pressure, with Fahmi directing MCMC to engage in public feedback. The question now looms: will Malaysia attempt internet fragmentation again in the future?

*A correction was made; "redirecting" not "centralising".

ICYMI: Exclusive access to paid subscribers only...

- Insight on Telegram Under Fire: Pavel Durov's Arrest and Implications.

Flashpoint on Deadly Mosque Attack Shocks Oman: Nine Dead as IS Claims Responsibility. - Insight on Navigating the Strategic and Policy Implications of Jemaah Islamiyah's Dissolution in Indonesia.

- Insight on Contextualising Al-Qaeda's Call To Arms and Implications for Southeast Asia's Militants.

- Flashpoint on U.S. Sanctions on Malaysian Semiconductor Trading Firm.

- Insight on Reassessing the Ulu Tiram Incident: The Subjectivity of Terror Labels.

- Insight on Jemaah Islamiyah Arrests in Sulawesi: Contextualising the Threat Perception by Alif Satria.

- Insight on India's Elections and Beyond: Balancing Nationalism with Global Aspirations by Hari Prasad.

- The Deep Dive on Shalom Avitan and Illicit Arms Trade in Malaysia's Periphery. A useful read to understand Thailand-Malaysia gunrunning.

- Flashpoint analysis on Iran-Israel Standoff: Navigating a No-Win Situation - Recent military exchanges between Israel and Iran have heightened regional tensions. What implications might this have for global stability?

Please feel free to share The Deep Dive with your colleagues. In addition, we would appreciate it if you could consider becoming a paid subscriber with our tiered subscription packages to support our publication. Your support will help us continue providing valuable insights to assist you in making operational decisions.